It’s funny how history repeats itself. A recent example of that was when I caught up with an old friend between recent trips. The phone conversation started like any other: Talk of family, vacations, mutual friends, and work, and how our favorite stick-and-ball sports teams have had lackluster seasons. Eventually the topic of automotive work and home garages arose.

My friend explained his son conjured the notion he could service the aging daily driver that shuttled him to and from a junior year of high school. Although the young man had no experience, online videos–like reality automotive restoration shows – made it look easy. He had already purchased oil and a correct filter, so how could my friend quell such money-saving motivation? After pointing out the correct tools, ramps, and jacking points on the car, he was sure his son would succeed.

“The constant banging I heard told my gut something was amiss, and I didn’t listen to myself because I was helping my daughter with math homework,” my friend explained. “Two hours later, my oil-covered son waltzed into the house and announced the job was done. Then he disappeared like he always does. I didn’t think anything of it until the next morning. The bent, oily screwdriver lying on the floor was the first clue it didn’t go well.

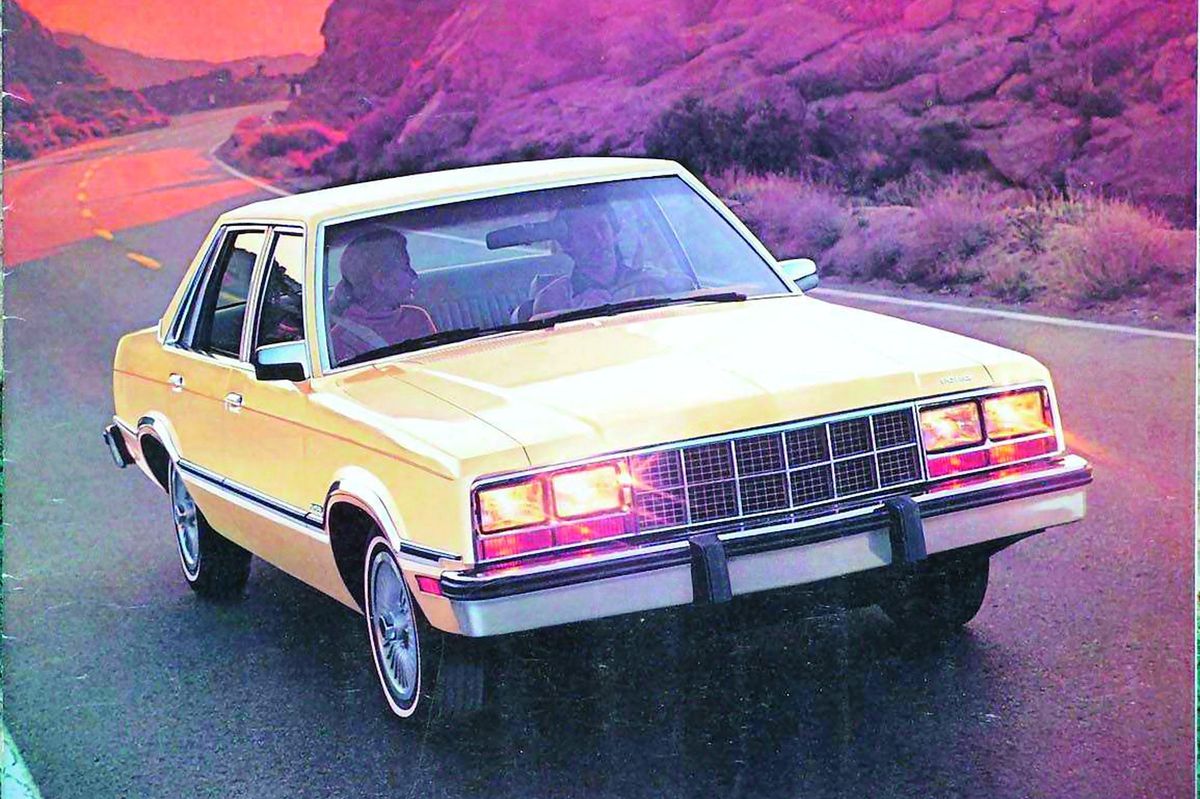

Enduro action circa 1989 begged our band of gearheads to turn a battered 1981 Ford Fairmont into a track warrior.

“I picked up the screwdriver and reached for the nearest rag on my workbench, except it was covered in oil, too. I took four steps to my cabinet to fetch a clean one and I nearly slipped in the puddle of oil on the floor. Catching my balance, the other foot knocked over the open pail of spent oil I didn’t see, and out rolled the twisted remains of a hole-riddled oil filter. There I am, slipping and sliding all over like Inspector Clouseau. That’s when I spotted the mangled oil wrench,” he said.

I didn’t have to be told that his son had difficulty with the oil wrench. Or that his next option was a hammer and screwdriver. I had seen that movie when I was in high school. A classmate attacked the oil filter on my 1983 Datsun Maxima with the same any-tool-will-work tenacity oozed by all-knowing 17-year-old boys. I was right under the car with him, and we got the job done, too.

This was when another classmate was driving a thoroughly used up 1981 Ford Fairmont Futura. Standing six-foot-five and tipping the scales at 275 pounds, it didn’t take long for the rear section of the driver’s seat track to fall through the floorboard. That alone should have raised a red flag about the car’s condition, but meager teenage incomes dictated another bout of “this-will-do” ingenuity in the form of a scrap of 2×4 lumber found on the side of the road.

That timber was still under the front seat when the alternator failed shortly after the Ford’s minor tussle with a stone wall. Rather than swap parts, he scoured local classifieds for an equally tarnished replacement car. New wheels seemed logical to both him and the rest of our little clan of gearheads, all of whom were weekly regulars at the local short track. It didn’t take long for us to consider turning the forlorn Fairmont into an enduro racer.

Unlike the 1913 Bugatti Type 22 gracing this month’s cover, a then-modern enduro rule book spelled out modest safety requirements. Gut the interior; weld the doors shut; install a roll cage; relocate the gas tank. And fix the alternator, courtesy of an ’82 Fairmont sedan we could obtain for $20. The whole car. Which meant a two-car team. One of us had a trailer, another had access to a welder. All that was left were fire suits, helmets, and a place to wrench. My childhood home in the countryside was perfect. Dad felt different when I broached the topic over dinner, and just like that, the whole sketchy high school race team scheme vaporized.

In hindsight, my dad saved us from ourselves, words I uttered as soon as my friend added, “And now he wants to build a race car, just like we wanted to back in high school.”